Champion and Gentleman – A short account of the life and achievements of one of Britain’s greatest amateur swimmers

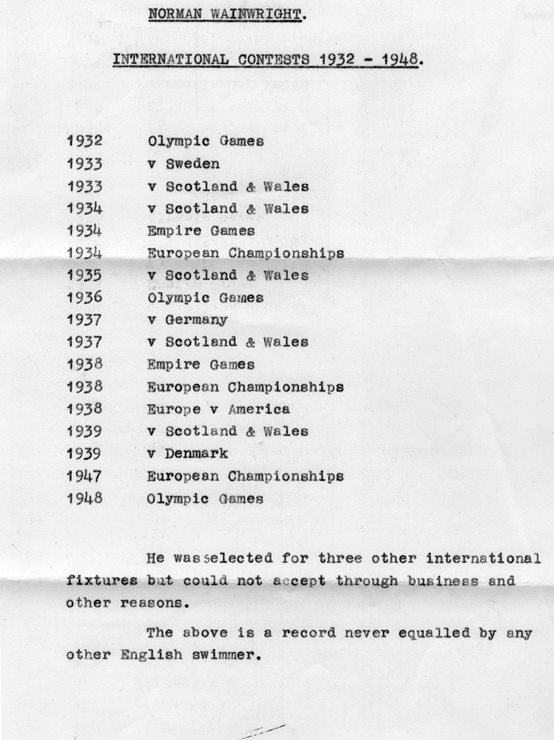

Norman Wainwright was a top national and international freestyle swimmer for most of the decade before the Second World War and, even after distinguished and debilitating war service overseas, he returned to represent his country. He competed in three Olympic Games (1932, 1936 & 1948); he won medals at two European and Empire Championships (1934 & 1938); was Amateur Swimming Association (ASA) champion 21 times; and held 50 ASA and British Native records. The picture to the left was taken in 1937 and shows Norman and his trainer, Harry Koskie with some of the trophies and medals he had won at that stage in his career. His achievement might have been greater if the Second World War had not intervened just as he was reaching the height of his powers. Even after his competitive swimming days were over (he retired in the early 1950’s, by which time he was approaching 40 years old), he continued to support his sport by serving on the Governing Bodies of the Staffordshire and Northern Counties ASA for more than twenty five years.

Norman Wainwright was a top national and international freestyle swimmer for most of the decade before the Second World War and, even after distinguished and debilitating war service overseas, he returned to represent his country. He competed in three Olympic Games (1932, 1936 & 1948); he won medals at two European and Empire Championships (1934 & 1938); was Amateur Swimming Association (ASA) champion 21 times; and held 50 ASA and British Native records. The picture to the left was taken in 1937 and shows Norman and his trainer, Harry Koskie with some of the trophies and medals he had won at that stage in his career. His achievement might have been greater if the Second World War had not intervened just as he was reaching the height of his powers. Even after his competitive swimming days were over (he retired in the early 1950’s, by which time he was approaching 40 years old), he continued to support his sport by serving on the Governing Bodies of the Staffordshire and Northern Counties ASA for more than twenty five years.

Norman was born on the 4th July 1914, the youngest of the four sons of William and Eliza Wainwright. His father was the manager of the Hanley Public Baths and he and his wife had come to this part of Stoke-on-Trent from their native Yorkshire, where he had worked as a physiotherapist at Harrogate Hydro. For Norman the swimming bath was his ‘back yard’. He learnt to swim when he was three and a half years old and began to win competitions from the time he went to school. He was also a good scholar and won a place at Hanley High School but did not have the opportunity to pursue higher education. Throughout his distinguished career, he had to balance training and competition with his work commitments and the only support he received was from friends and colleagues. Thus his outstanding achievements were earned in a very different world to that of the sponsorship enjoyed by the top athletes of today and even then contrasted with the patronage and support received by some of those competing against him.

Norman was born on the 4th July 1914, the youngest of the four sons of William and Eliza Wainwright. His father was the manager of the Hanley Public Baths and he and his wife had come to this part of Stoke-on-Trent from their native Yorkshire, where he had worked as a physiotherapist at Harrogate Hydro. For Norman the swimming bath was his ‘back yard’. He learnt to swim when he was three and a half years old and began to win competitions from the time he went to school. He was also a good scholar and won a place at Hanley High School but did not have the opportunity to pursue higher education. Throughout his distinguished career, he had to balance training and competition with his work commitments and the only support he received was from friends and colleagues. Thus his outstanding achievements were earned in a very different world to that of the sponsorship enjoyed by the top athletes of today and even then contrasted with the patronage and support received by some of those competing against him.

Local rivalry was the spur that encouraged the young Wainwright to make the effort to compete at national and international level. Bob Leivers, who swam for the Longton Swimming Club, was six months younger than Norman but he achieved national prominence first (he won his first ASA titles in 1932). Norman, who competed for Hanley, persuaded his eldest brother, George (who had followed his father into Baths management), to help him with his training. During the winter of 1931/32, Bob Leivers and Norman Wainwright also received guidance from the Northern Counties coach, Jack Laverty (the picture above, taken in 1931, shows Norman with his father, both to the left of the photograph, with Bob Leivers and –possibly– his father). The result was that in 1932 both were selected to swim for Great Britain in the Olympic Games that were to be held in Los Angeles, California. In those days, this involved a long journey by sea and rail. Sadly, Norman’s father had died shortly before he could enjoy the pleasure of his son’s achievements.

Local rivalry was the spur that encouraged the young Wainwright to make the effort to compete at national and international level. Bob Leivers, who swam for the Longton Swimming Club, was six months younger than Norman but he achieved national prominence first (he won his first ASA titles in 1932). Norman, who competed for Hanley, persuaded his eldest brother, George (who had followed his father into Baths management), to help him with his training. During the winter of 1931/32, Bob Leivers and Norman Wainwright also received guidance from the Northern Counties coach, Jack Laverty (the picture above, taken in 1931, shows Norman with his father, both to the left of the photograph, with Bob Leivers and –possibly– his father). The result was that in 1932 both were selected to swim for Great Britain in the Olympic Games that were to be held in Los Angeles, California. In those days, this involved a long journey by sea and rail. Sadly, Norman’s father had died shortly before he could enjoy the pleasure of his son’s achievements.

Although he did not make the finals, the Olympics were valuable experience and a great personal adventure. While he was there, he became the fastest British swimmer at the 400-metre freestyle but he also received a tour of the Hollywood film studios, as the picture shows. The following year he won his first ASA championships (at half mile and one mile, freestyle) and was a member of the England Team that competed against Sweden. He also started to collect ASA and British Native records. ASA titles and records are open to all comers and the records represent the fastest time put up in England by any swimmer, regardless of nationality. In 1933 swimmers from outside the UK held many of these and Norman deliberately set out to beat their times so that all the records would be in British hands.

Although he did not make the finals, the Olympics were valuable experience and a great personal adventure. While he was there, he became the fastest British swimmer at the 400-metre freestyle but he also received a tour of the Hollywood film studios, as the picture shows. The following year he won his first ASA championships (at half mile and one mile, freestyle) and was a member of the England Team that competed against Sweden. He also started to collect ASA and British Native records. ASA titles and records are open to all comers and the records represent the fastest time put up in England by any swimmer, regardless of nationality. In 1933 swimmers from outside the UK held many of these and Norman deliberately set out to beat their times so that all the records would be in British hands.

In 1934 he represented England at Wembley in the Empire Games and was 2nd in the 440  yards. Only a week later he was part of the British Team at Magdeburg, Germany for the European Championships (the picture to the left shows the British Team at the opening parade – note the Nazi salutes given by the onlookers) and was the only British free style swimmer to be placed (he won a Bronze Medal at 1500 metres). During this period, it was calculated that Norman swam twice as far as all the other 17 members of the team put together. In the same year he also captured the 500 yards ASA title (from Bob Leivers, who had won it in 1932 and 33 – incidentally this was the last occasion on which this distance was recognised by the ASA for championship purposes) and retained the mile and half mile championships. Another highlight of 1934 was that he first captained England (when only aged twenty) in a match versus Scotland and Wales. Also in the same year, while representing England v. Denmark, he created a new Danish record for 400 metres.

yards. Only a week later he was part of the British Team at Magdeburg, Germany for the European Championships (the picture to the left shows the British Team at the opening parade – note the Nazi salutes given by the onlookers) and was the only British free style swimmer to be placed (he won a Bronze Medal at 1500 metres). During this period, it was calculated that Norman swam twice as far as all the other 17 members of the team put together. In the same year he also captured the 500 yards ASA title (from Bob Leivers, who had won it in 1932 and 33 – incidentally this was the last occasion on which this distance was recognised by the ASA for championship purposes) and retained the mile and half mile championships. Another highlight of 1934 was that he first captained England (when only aged twenty) in a match versus Scotland and Wales. Also in the same year, while representing England v. Denmark, he created a new Danish record for 400 metres.

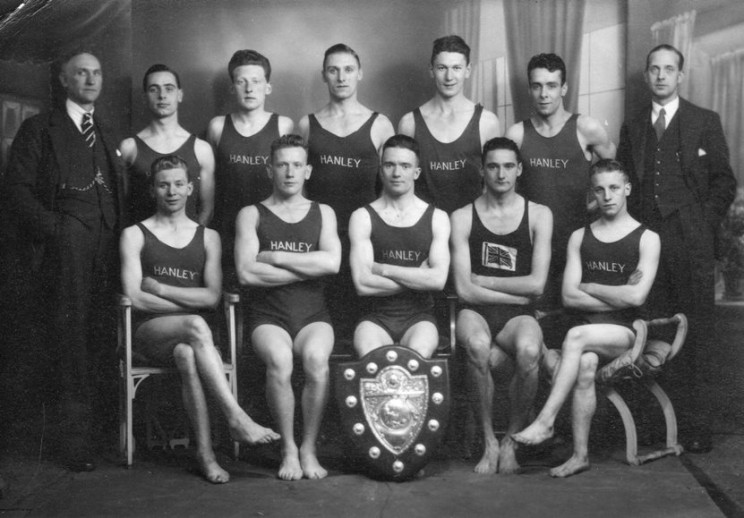

Thus, before he was considered to have reached adulthood (which in those times meant being over 21) he had achieved national and international recognition. However, what is especially remarkable is that he was an amateur without wealth of his own or the financial support of his family. He had started work directly after leaving school and it was expected that the requirements of the job should come before his swimming career. After his father died, his mother had to leave Hanley Baths (because the accommodation went with her husband’s job). Thus Norman lost both home and training facilities. Fortunately, fellow members of Hanley Swimming Club (see picture above) tried to help. One of them, Harry Koskie (centre, front row, with Norman sitting next left in the picture), became his trainer in 1933 and he and his wife Olive gave considerable personal support. He used to live with them while in training and they ensured that he had what was then thought to be the appropriate diet. A prominent local businessman and supporter of the Club, Geoff Corn, found Norman a job at his firm, Richards Tiles. Even so, training had to be done before and after work and he was expected to earn the concessions given to allow him to compete. For example, there were times when he came back from a trip overseas and went straight to work, regardless of whether he had been able to get adequate sleep. Also, when he represented his Country at the Empire Games in Australia, he stayed out there for six months, selling for Richards Tiles. Because the Company was a major producer of the tiles used to line swimming pools, Norman Wainwright’s reputation as a swimmer was a significant asset to them but he was also technically well versed and eventually rose to be a senior executive.

Thus, before he was considered to have reached adulthood (which in those times meant being over 21) he had achieved national and international recognition. However, what is especially remarkable is that he was an amateur without wealth of his own or the financial support of his family. He had started work directly after leaving school and it was expected that the requirements of the job should come before his swimming career. After his father died, his mother had to leave Hanley Baths (because the accommodation went with her husband’s job). Thus Norman lost both home and training facilities. Fortunately, fellow members of Hanley Swimming Club (see picture above) tried to help. One of them, Harry Koskie (centre, front row, with Norman sitting next left in the picture), became his trainer in 1933 and he and his wife Olive gave considerable personal support. He used to live with them while in training and they ensured that he had what was then thought to be the appropriate diet. A prominent local businessman and supporter of the Club, Geoff Corn, found Norman a job at his firm, Richards Tiles. Even so, training had to be done before and after work and he was expected to earn the concessions given to allow him to compete. For example, there were times when he came back from a trip overseas and went straight to work, regardless of whether he had been able to get adequate sleep. Also, when he represented his Country at the Empire Games in Australia, he stayed out there for six months, selling for Richards Tiles. Because the Company was a major producer of the tiles used to line swimming pools, Norman Wainwright’s reputation as a swimmer was a significant asset to them but he was also technically well versed and eventually rose to be a senior executive.

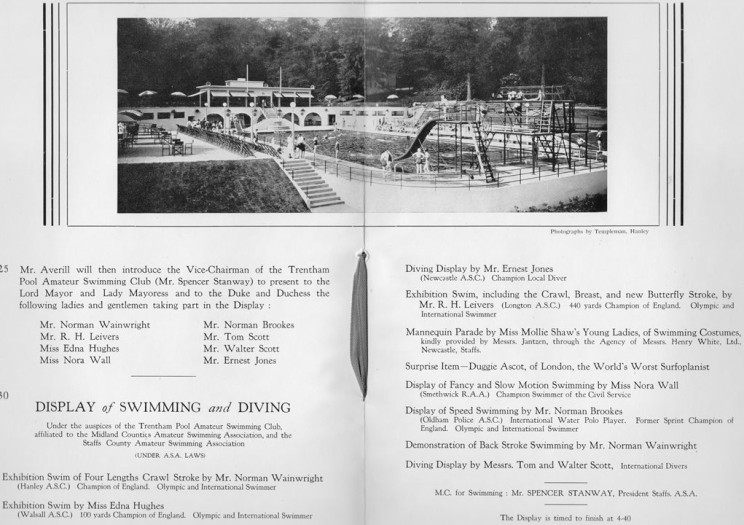

1935 proved to be an outstanding year. During a tour of the Continent, he defeated the champions of five different countries and established new records in Switzerland and Holland. He concluded by beating a Dutch relay team of four swimmers. He also swam for England v. Scotland and Wales again. Despite his international results and record times, he had not succeeded in winning the ASA quarter mile championship. However, in 1935 he not only achieved this ambition but also captured the 220 yards title for the first time. He retained his mile and half mile championships, thus holding each of these titles for the third successive year. As the picture above shows, he also took part in the opening ceremony for Trentham Gardens Open-Air Swimming Pool (now demolished), which became his new training base.

1935 proved to be an outstanding year. During a tour of the Continent, he defeated the champions of five different countries and established new records in Switzerland and Holland. He concluded by beating a Dutch relay team of four swimmers. He also swam for England v. Scotland and Wales again. Despite his international results and record times, he had not succeeded in winning the ASA quarter mile championship. However, in 1935 he not only achieved this ambition but also captured the 220 yards title for the first time. He retained his mile and half mile championships, thus holding each of these titles for the third successive year. As the picture above shows, he also took part in the opening ceremony for Trentham Gardens Open-Air Swimming Pool (now demolished), which became his new training base.

The focus of 1936 was the Olympic Games in Berlin, often remembered as “Hitler’s Olympics” because of the German Dictator’s determination to use the event to prove the superiority of his people. Norman won the ASA 220 and 440-yard championships before the Games. More significantly, he was the first Briton to break the five-minute mark for both 400 metres and 440 yards and this placed him among the fastest swimmers in the world at these distances. At the Olympics, he would be up against strong German opposition in his events. However, he was destined to miss out on a place in the finals again (he is shown above, winning his heat) because he was affected by a mystery stomach ailment. His trainer, Harry Koskie, suspected ‘foul play’. He was so ill that he could not defend his mile and half-mile ASA titles after the Games and there were even fears that his career could be over, at the age of twenty-two.

The focus of 1936 was the Olympic Games in Berlin, often remembered as “Hitler’s Olympics” because of the German Dictator’s determination to use the event to prove the superiority of his people. Norman won the ASA 220 and 440-yard championships before the Games. More significantly, he was the first Briton to break the five-minute mark for both 400 metres and 440 yards and this placed him among the fastest swimmers in the world at these distances. At the Olympics, he would be up against strong German opposition in his events. However, he was destined to miss out on a place in the finals again (he is shown above, winning his heat) because he was affected by a mystery stomach ailment. His trainer, Harry Koskie, suspected ‘foul play’. He was so ill that he could not defend his mile and half-mile ASA titles after the Games and there were even fears that his career could be over, at the age of twenty-two.

Perhaps justice was done, in small measure, in 1937. During an England v. Germany match at Wembley (see picture to left), Norman won his individual event (beating the German Champion Werner Plath) and then swam the last leg of the 200 metres relay and was set the task of catching Helmut Fischer, the European Record Holder, who had a substantial lead. It appeared a forlorn hope, but Norman put up one of the most memorable efforts of his career and won by inches, to the delight of 10,000 madly excited spectators. Earlier in the year, he had retained his ASA 220 & 440-yard championships and recaptured the mile and half mile titles. He also broke the 150 yards ASA record and, thereby, removed the last foreign name from the Record Book.

Perhaps justice was done, in small measure, in 1937. During an England v. Germany match at Wembley (see picture to left), Norman won his individual event (beating the German Champion Werner Plath) and then swam the last leg of the 200 metres relay and was set the task of catching Helmut Fischer, the European Record Holder, who had a substantial lead. It appeared a forlorn hope, but Norman put up one of the most memorable efforts of his career and won by inches, to the delight of 10,000 madly excited spectators. Earlier in the year, he had retained his ASA 220 & 440-yard championships and recaptured the mile and half mile titles. He also broke the 150 yards ASA record and, thereby, removed the last foreign name from the Record Book.

In 1937 The City of Stoke-on-Trent honoured its two famous international swimmers, Leivers and Wainwright but at the end of the year Norman sailed for Australia so that he could compete in the 1938 Empire Games where he won a gold medal. For business reasons, explained above, he did not return to Britain until July and then had less than a fortnight to prepare for the National Championships but still succeeded in retaining his titles at 220 and 440 yards, on successive days against strong competition! Later in the same year he took part in the European Championships at Wembley and won another Bronze medal. As a result, he was selected to swim for Europe, as part of the 200 metres relay team, in the inter-continental games versus America at

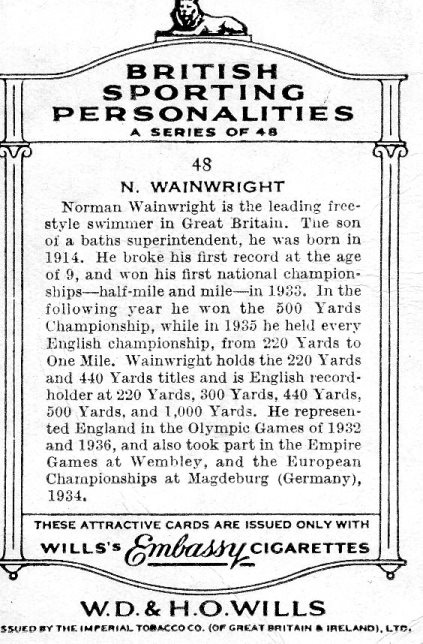

In 1937 The City of Stoke-on-Trent honoured its two famous international swimmers, Leivers and Wainwright but at the end of the year Norman sailed for Australia so that he could compete in the 1938 Empire Games where he won a gold medal. For business reasons, explained above, he did not return to Britain until July and then had less than a fortnight to prepare for the National Championships but still succeeded in retaining his titles at 220 and 440 yards, on successive days against strong competition! Later in the same year he took part in the European Championships at Wembley and won another Bronze medal. As a result, he was selected to swim for Europe, as part of the 200 metres relay team, in the inter-continental games versus America at  Budapest. He was also celebrated on a ‘cigarette card’ – see left. In October 1938, he married Alice Elizabeth (Betty) Porter and they settled in the village of Trentham. They had one child, Elisabeth (born in November 1946 after he returned from war service).

Budapest. He was also celebrated on a ‘cigarette card’ – see left. In October 1938, he married Alice Elizabeth (Betty) Porter and they settled in the village of Trentham. They had one child, Elisabeth (born in November 1946 after he returned from war service).

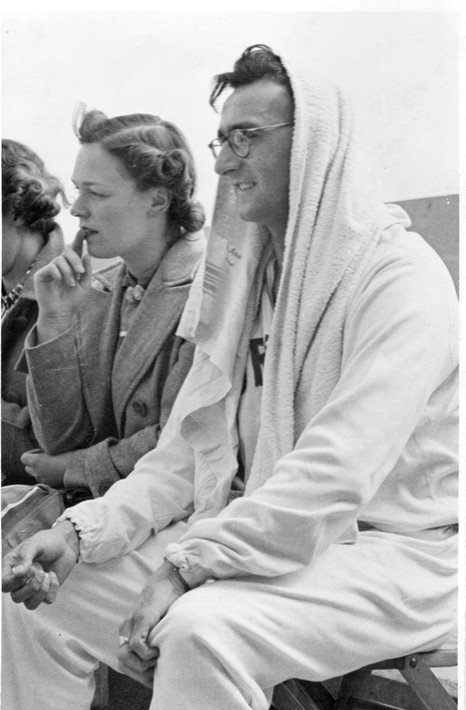

1939 saw the outbreak of the Second World War, just as Norman was approaching his best. He won the ASA freestyle championships at a furlong (i.e. 220 yards) quarter, half and one mile. Thus, he held the titles for the two shorter distances for the fifth successive time and also brought to five the number of times that he had won the other two events. With his 1934 victory at 500 yards, this completed his collection of 21 ASA championships. His times were also among the best recorded anywhere in the world and it had been anticipated that he would have been at his peak for the 1940 Olympic Games, which was never held. He is shown, to the right, above, in 1939, sitting at the poolside with his wife.

as Norman was approaching his best. He won the ASA freestyle championships at a furlong (i.e. 220 yards) quarter, half and one mile. Thus, he held the titles for the two shorter distances for the fifth successive time and also brought to five the number of times that he had won the other two events. With his 1934 victory at 500 yards, this completed his collection of 21 ASA championships. His times were also among the best recorded anywhere in the world and it had been anticipated that he would have been at his peak for the 1940 Olympic Games, which was never held. He is shown, to the right, above, in 1939, sitting at the poolside with his wife.

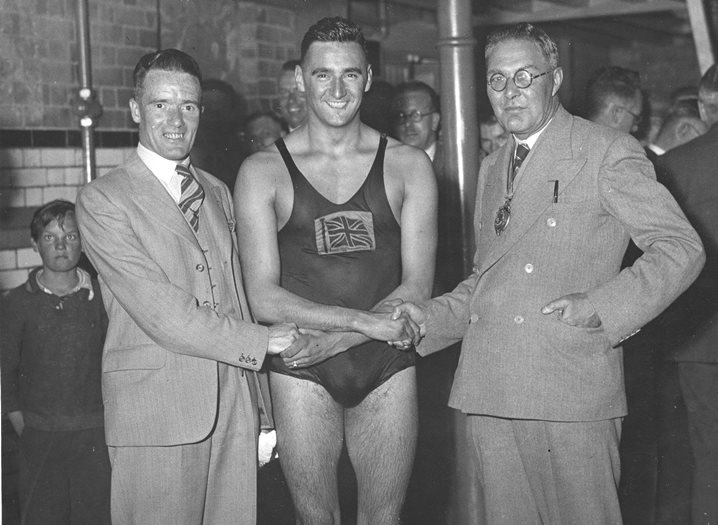

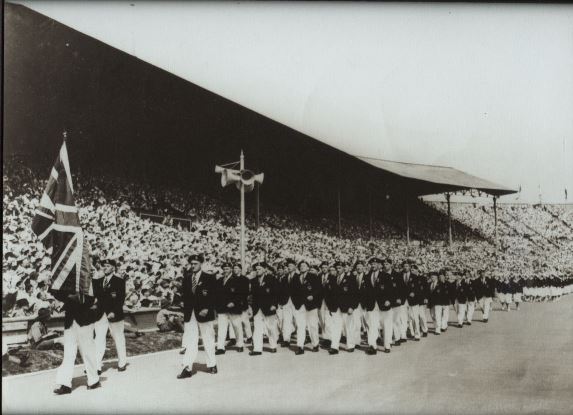

The first major post-war event was the European Olympia at Monte Carlo, where, despite his age and time spent in the debilitating war-time conditions of Iraq, Norman proved to be the best Briton over 200 metres; remarkably, his time equalled his 1938 European Championship effort. This led to his selection for the British Team at the 1948 Olympics, as part of the 200 metres relay squad. He was honoured with the captaincy of the Swimming Team and, as a survivor from the pre-war Games, was one of the three British athletes who led the opening procession into Wembley Stadium – pictured above.

The first major post-war event was the European Olympia at Monte Carlo, where, despite his age and time spent in the debilitating war-time conditions of Iraq, Norman proved to be the best Briton over 200 metres; remarkably, his time equalled his 1938 European Championship effort. This led to his selection for the British Team at the 1948 Olympics, as part of the 200 metres relay squad. He was honoured with the captaincy of the Swimming Team and, as a survivor from the pre-war Games, was one of the three British athletes who led the opening procession into Wembley Stadium – pictured above.

He adjusted to his retirement from swimming with the same equanimity that he had accepted the fortunes of competition and concentrated on helping others whether in the pool or through administration of the sport. For example, he took on the thankless task of being unpaid Treasurer of Staffordshire ASA for a quarter of a century (a feat celebrated in the local newspaper The Sentinel in 1981, when he retired). As he grew older, he often expressed surprise when he was asked to appear at events or be interviewed by the media. He felt that he had had his time and the glory should go to the younger generation.

He adjusted to his retirement from swimming with the same equanimity that he had accepted the fortunes of competition and concentrated on helping others whether in the pool or through administration of the sport. For example, he took on the thankless task of being unpaid Treasurer of Staffordshire ASA for a quarter of a century (a feat celebrated in the local newspaper The Sentinel in 1981, when he retired). As he grew older, he often expressed surprise when he was asked to appear at events or be interviewed by the media. He felt that he had had his time and the glory should go to the younger generation.

Despite being crippled by a combination of heart disease and arthritis in his latter years and finally, having to endure treatment for cancer, he was a positive inspiration to all those around him. His swimming achievements are a memorial to an outstanding national and international champion. However, his other legacy, given by example, was that in life you should prepare well and give your best to every endeavour but then accept all outcomes with equal equanimity. He came to his rest on 2nd May 2000, in his 86th year, leaving behind his wife Betty (pictured with him in a photograph taken for a local magazine), daughter Elisabeth, grandson Christopher and other family and friends to regret his passing but be glad and privileged to have known this “Champion and Gentleman”.

Despite being crippled by a combination of heart disease and arthritis in his latter years and finally, having to endure treatment for cancer, he was a positive inspiration to all those around him. His swimming achievements are a memorial to an outstanding national and international champion. However, his other legacy, given by example, was that in life you should prepare well and give your best to every endeavour but then accept all outcomes with equal equanimity. He came to his rest on 2nd May 2000, in his 86th year, leaving behind his wife Betty (pictured with him in a photograph taken for a local magazine), daughter Elisabeth, grandson Christopher and other family and friends to regret his passing but be glad and privileged to have known this “Champion and Gentleman”.

Paul Newman

(Son-in-law to Norman Wainwright)